Far-reaching rules governing the use of artificial intelligence (AI) currently look set to come into force in the European Union (EU) in 2025 or 2026. The Council of the EU’s 27 member states and the European Parliament have recently pitched various amendments to the European Commission’s April 2021 proposal for regulating “high-risk” uses of AI and are hammering out a common text. Depending on the length of these talks, both EU bodies could pass the AI Act in 2023 or 2024 and the so-called horizontal regulation – one that cuts across all areas of AI use, rather than focusing on specific ones – take effect two years later.

This means many details of what will be the world’s most comprehensive AI regulation are still in flux. But much of its outline is clear – as are areas in which the devil could yet lie in the detail. The AI Act establishes a compliance framework that will mean more (paper)work and higher costs for developers of what the EU deems high-risk AI applications – regardless of whether they’re based in the EU or only serve customers there. Even if the Commission estimates that only 5-15 percent of applications will be classed as high risk, bigger players will have less trouble coping than the smaller ones without lawyers in house or on call.

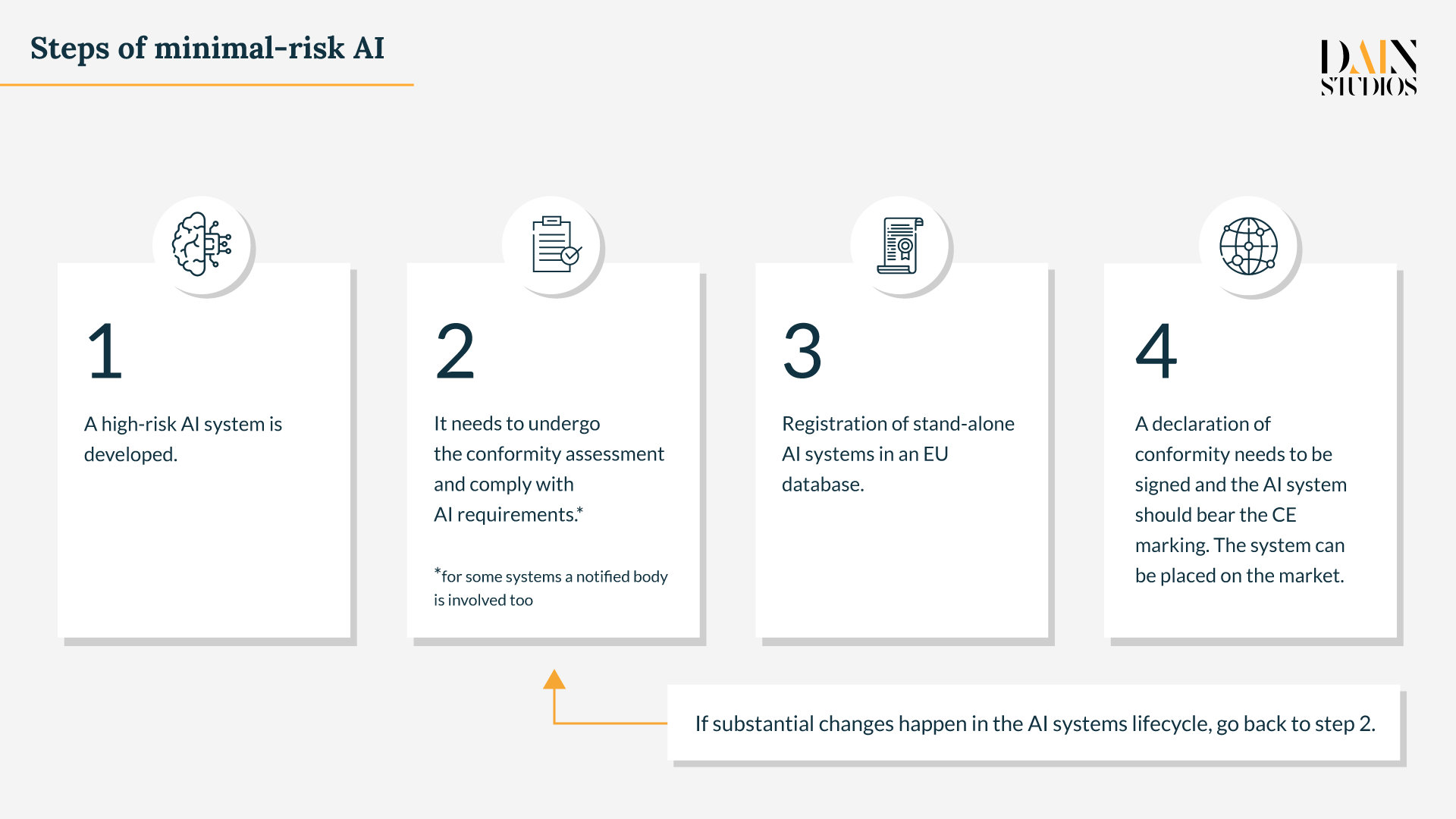

The Commission’s draft regulation, for example, defines any company developing an AI system as an “AI provider” – by implication also any company creating an AI system for internal use only. Should that company want to use this application for personnel management, education or other so-called high-risk applications, it would have to conduct a conformity assessment before doing so and monitor its performance thereafter. Any unwitting “AI provider” oblivious of this rule would face a fine (see below) if it had not secured the mandatory CE-mark as proof the product conforms to EU health, safety and environmental standards.

This potential legal pitfall is aggravated by a necessarily very broad definition of AI chosen by the Commission. Aside from machine-learning, it considers any piece of software using long-established expert systems and statistical models as integral to AI. This means even simple forms of code could fall within the purview of the AI Act – and require a declaration of conformity from a third party if they were used in high-risk areas. But, this and other problems in the draft regulation have been identified – and the hope now is that the EU member states and European Parliament will attend to the areas that need attention.

Though details are in flux, AI Act’s broad outline is clear

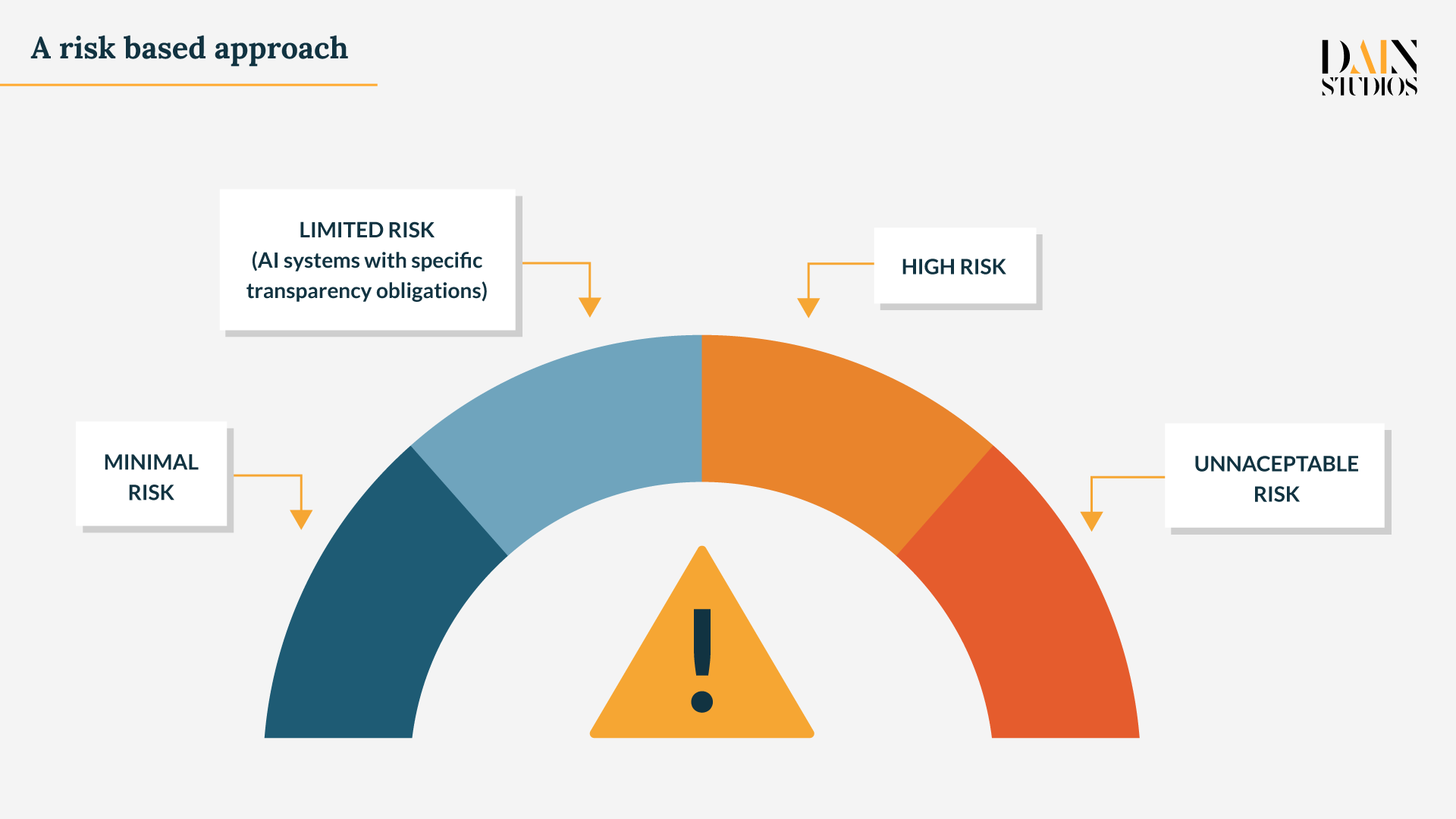

What’s clear is that the EU AI Act will create an AI product-safety framework based on four risk categories. Chatbots, spam filters, inventory-management or customer-segmentation systems are defined as minimal or no risk applications and will not be regulated. At the other extreme, AI-driven applications for social scoring, manipulating behavior, causing bodily or psychological harm or real-time remote biometric identification of people in public spaces are defined as unacceptably risky and will be banned outright (although there will probably be a contentious exemption to allow biometric ID for certain vital police work).

Between these poles come AI-driven products that are permitted, but which underlie certain information and transparency obligations. Ultra-realistic bots that interact with humans, applications that detect emotions or determine associations with social categories based on biometric data, computer-generated images – so-called deepfake photographs, film clips or sound snippets – need to be flagged as being the products of AI. This allows users to desist from interacting with such AI-based products if they do not want their emotions assessed or do not want to watch or listen to partly or wholly fictional content.

Lastly, there are AI-driven products that are considered high risk, but permitted. They can only be made available to users if they have proven themselves in compliance with EU rules for high-risk AI. Solutions that use biometric identification and categorisation, manage critical infrastructure (like traffic and electricity), manage or recruit personnel, control access to private services (like bank loans) or public services and benefits, help with law enforcement, migration, asylum, border control and the administration of justice will all require a CE product-safety mark before they can be marketed commercially to users.

This means AI providers in financial services, education, employment and human resources, law enforcement, industrial AI, medical devices, cars, machinery, toys will not only have to prove their products meet the EU’s requirements as they hit the market. Before this even happens, they will have to prove that their machine-learning training, testing and validation datasets meet EU standards. AI has to be legally, ethically and technically robust, while respecting democratic values, human rights and the rule of law. The AI Act is founded on the premise that if users know they can trust AI, the technology will gain wide acceptance.

Ten new compliance “to-dos” for developers of high-risk AI

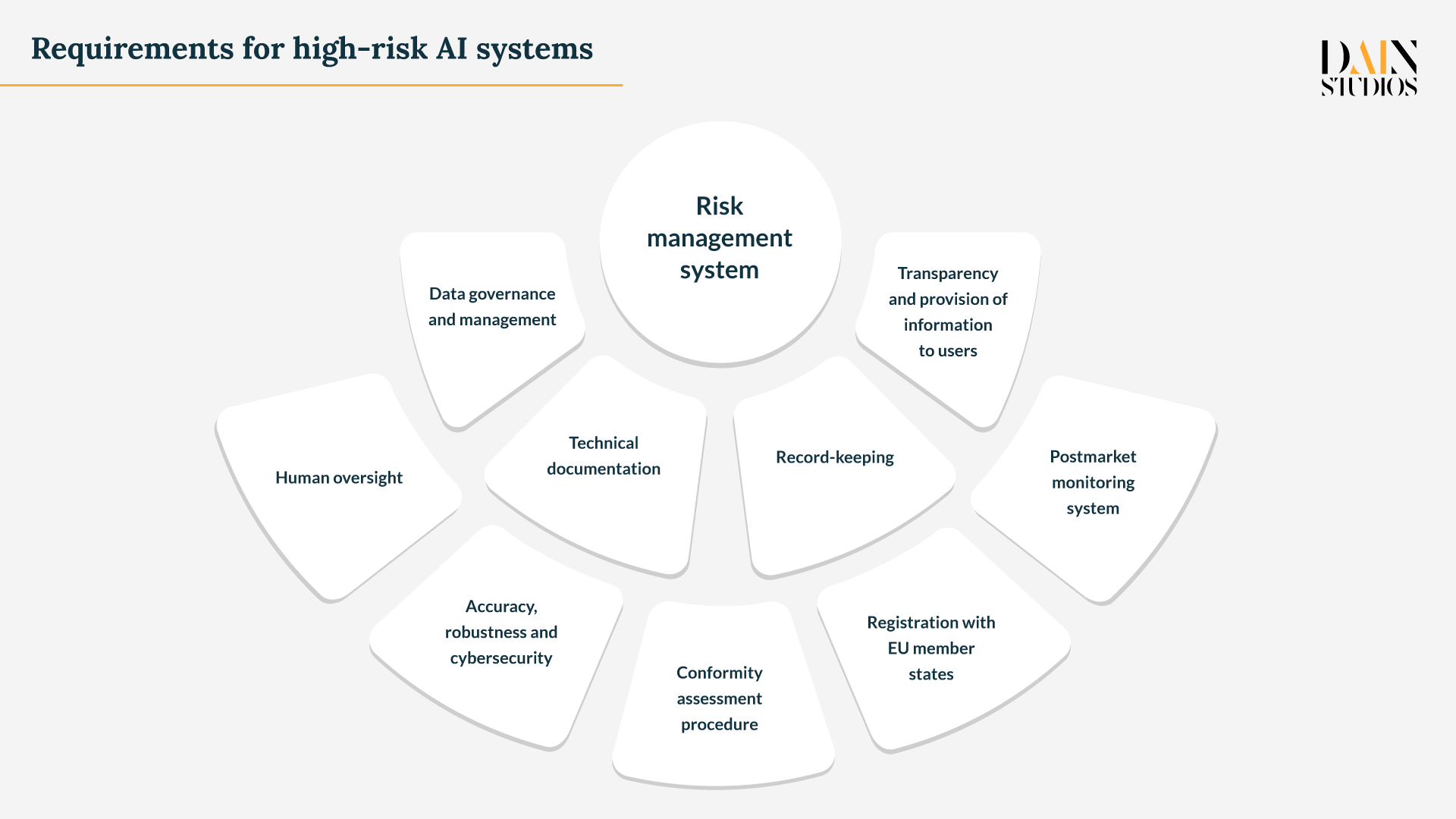

The draft regulation published a year ago puts most obligations regarding high-risk AI systems on AI providers – although distributors, importers users “or any other third party” will fall under the same requirements if they market an AI-based product under their name or brand or modify its purpose or make substantial modifications. The regulation is a legal act that will apply automatically and uniformly in all EU countries – and member states will also be responsible for the enforcement of the AI Act’s rules. Specifically, providers of high-risk AI-driven products and systems will be required to establish and maintain:

- a risk management system that addresses the AI-system’s risks,

- a system for ensuring data governance and management,

- technical documentation, beginning with a general description of the product,

- record keeping through automatic recording of events,

- transparency about the AI used and provision information to users,

- effective human oversight of the AI system and its decision-making,

- accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity of the AI system,

- a conformity assessment procedure before being used,

- product registration with EU member states through the CE-mark,

- post-market monitoring to enable corrective action if the AI proves non-compliant.

This is a long list, still unhelpfully vague in places. For example, the data governance and management section stipulates only vague quality criteria for training, testing and validation data sets – they should be subject to “appropriate data governance and management practices.” On the other hand, requirements like understanding risk and communicating algorithms are already part of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force in 2018. AI providers have to give a description of the AI system, including its intended purpose, the people developing it and how it interacts with other hardware or software.

The groundbreaking GDPR is in many ways an important precedent for the AI Act. Software developers have learned to factor in the EU’s data-privacy rules into their work – and there is every reason to think they will do the same with the AI regulation. Here as there, the rules will raise costs for some players, but will also create new opportunities for businesses offering compliance services. Lastly, the AI Act codifies many best practices that are already in use (and everyone should be using). Transparency and “explainability” are crucial to combating public fears about AI, nothing less than prerequisites for keeping the sector in business.

Fines for non-compliance – and the costs for conforming

The AI Act’s sanctions for non-compliance are familiar from GDPR. Companies can be fined:

- up to €10m or 2% of worldwide annual turnover (whichever is higher) for incorrect, incomplete or misleading information in response to a request from authorities,

- up to €20m or 4% for non-compliance with most requirements or obligations,

- up to €30m or 6% for infringements of or non-compliance with data requirements.

Looking at the cost side, the Commission’s 2021 Impact Assessment suggested that compliance costs for high-risk AI could be similar to the costs of implementing GDPR – with the caveat that AI Act’s compliance costs would be in part recurring because of the need to monitor (and possibly adapt and then review the conformity of) each AI system. It estimated compliance costs would hit 4-5 percent of software costs, with maximum aggregate costs for high-risk AI applications hitting E100 million to E500 million in 2025. The implication is that an industry that dealt with the burdens of GDPR will also weather the costs of the AI Act.

But the Commission’s draft regulation does include some caveats for SMEs and startups. For example, it obliges EU member states to give small-scale providers and start-ups priority access to AI regulatory sandboxes and take the interests and needs of small-scale providers into account when setting the conformity-assessment fees. In addition, national authorities are asked to “take into particular account the interests of small-scale providers and start-up and their economic viability” in the event of setting penalties. As the AI Act is also meant to stimulate AI investment, it will be interesting to see how it ultimately treats smaller players.

One of the most important messages of the AI Act is that AI systems are not intentionally malicious – but that they can have huge direct and indirect negative impacts on the environments in which they operate because of their traditional lack of transparency and ever-growing scale. The AI industry needs to be aware of this problem, set standards to counter it and work on regulation. And if the EU’s AI Act can help it along this path, the industry should face up to it in a constructive manner. For the EU, the trick will be to introduce regulation that raises trust in the industry as a whole without privileging the larger over the smaller players.